FlakPhoto Digest is a free, reader-supported publication. Writing this newsletter takes hours of work. If you appreciate my writing, consider becoming a paid subscriber. For $5/month, paid subscriptions keep the FlakPhoto project going. Thanks so much for your financial support. I appreciate it! Hey, Friends, it’s almost that time of year: Christmas is coming! I wanted to share a new Show & Tell with you before we break for the holidays and give you something to read while you’re sipping coffee (or egg nog) by the tree over the next few days. There is a lot to look at and think about here. I hope you like it.🎄❄️✨ — AA I’m excited about today’s conversation because it offers a far-ranging look inside the mind of a creative person I have admired for a while. I’m a photography geek who looks at the credits, and when I noticed this striking portrait of the great writer Rebecca Solnit in the New York Times a few years ago (here’s a gift link if you want to read it), I was immediately intrigued. Trent Davis Bailey can really see. Today’s Show & Tell is part of an ongoing series of conversations with imagemakers about the art and ideas that inspire them. You can read my previous interviews with Jess T. Dugan and Jon Horvath. Is there an artist you’d like me to interview? Please email your suggestions anytime. I’m always looking, and I love hearing from you. With that, I’ll let Trent take it from here. This one’s a deep dive, so relax, sit back, and enjoy. Tell us about yourself. Where are you from, and where do you live now? Hi Andy! Thanks for having me. I grew up in the suburbs southwest of Denver, Colorado. I now live in Evergreen, a mountain town near Denver that’s seasonally home to more deer and elk than humans. When I was younger, I swore I’d move away from where I grew up, and I did for a time. I lived and worked in New York City for three years in my mid-twenties and then moved to San Francisco in 2013 to attend graduate school at the California College of the Arts. During my eight years in those two coastal cities, I regularly returned inland to Colorado to photograph and visit family. I can see now it was inevitable that I’d move back. Even though I’ve been here for six years, my younger self can hardly believe my current home is only a 30-minute drive from my childhood home. Could you describe your photography? What inspired you to pursue this art form? My photography takes a long view on memory and geography, particularly as they relate to ecology, place, landscape, and time. I don’t follow a single methodology, nor do I force meaning upon the work; instead, I allow the work to reveal itself to me slowly. If I had to pinpoint the moment I first became inspired to pursue photography, it would be when I was tied to a tree. My older brother’s high school art teacher had assigned his class to make pictures that included a rope. His response was to bind me — then twelve years old — to an old cottonwood in our family’s backyard. After the tree, we conspired to tie me to the roof of my dad’s old Toyota Land Cruiser. He made some more exposures, put the keys in the ignition, and we went for a ride around the block. We had never acted in such an uninhibited way before. It was as if my brother and I were characters in a fiction based on the reality of our lives. Our impulsiveness and complicity startled me. It made me want to get a camera and make my own pictures. Unfortunately, the prints and negatives from our photoshoot were unsalvageable after our family’s basement flooded in the summer of ‘99, but the story lives on.

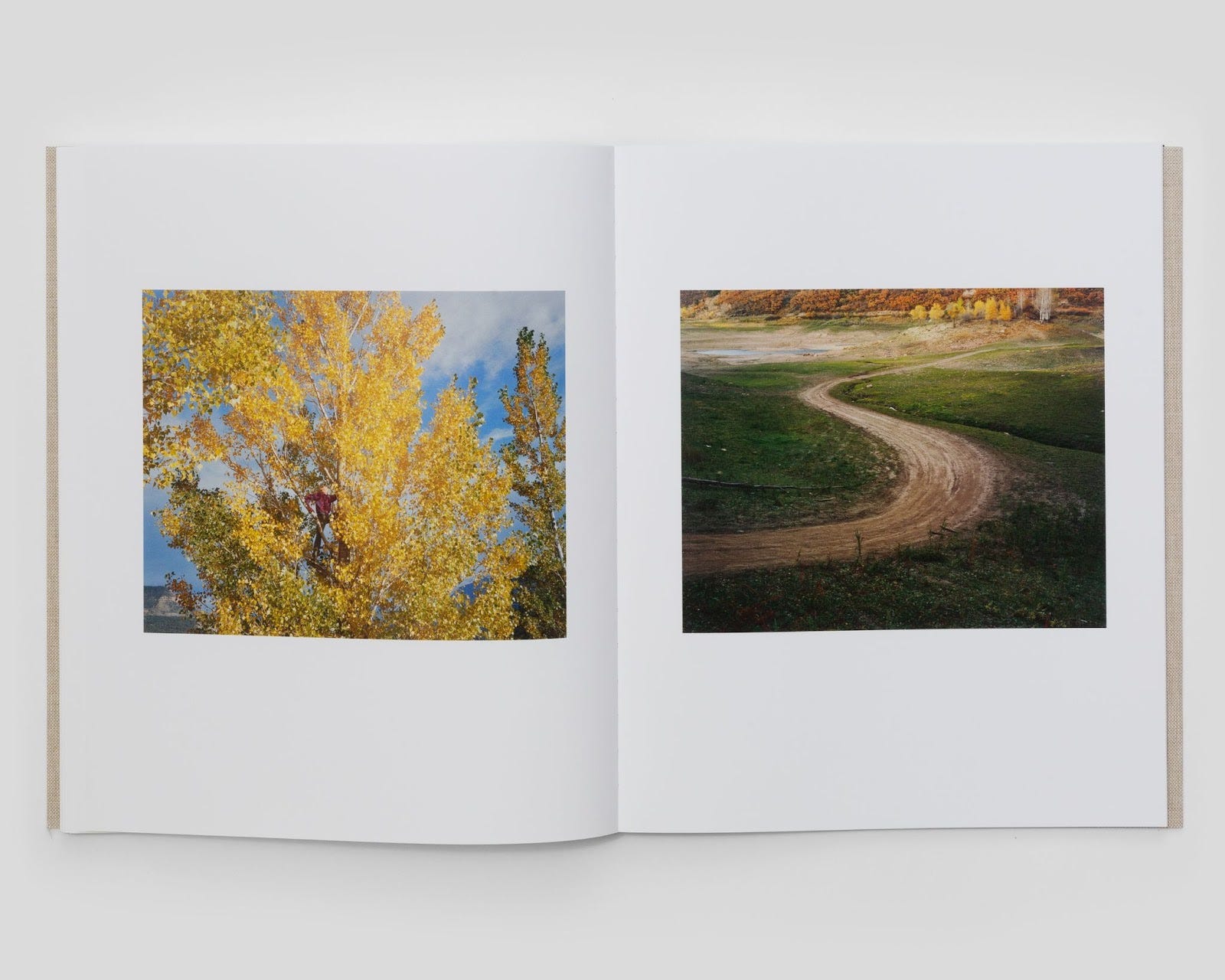

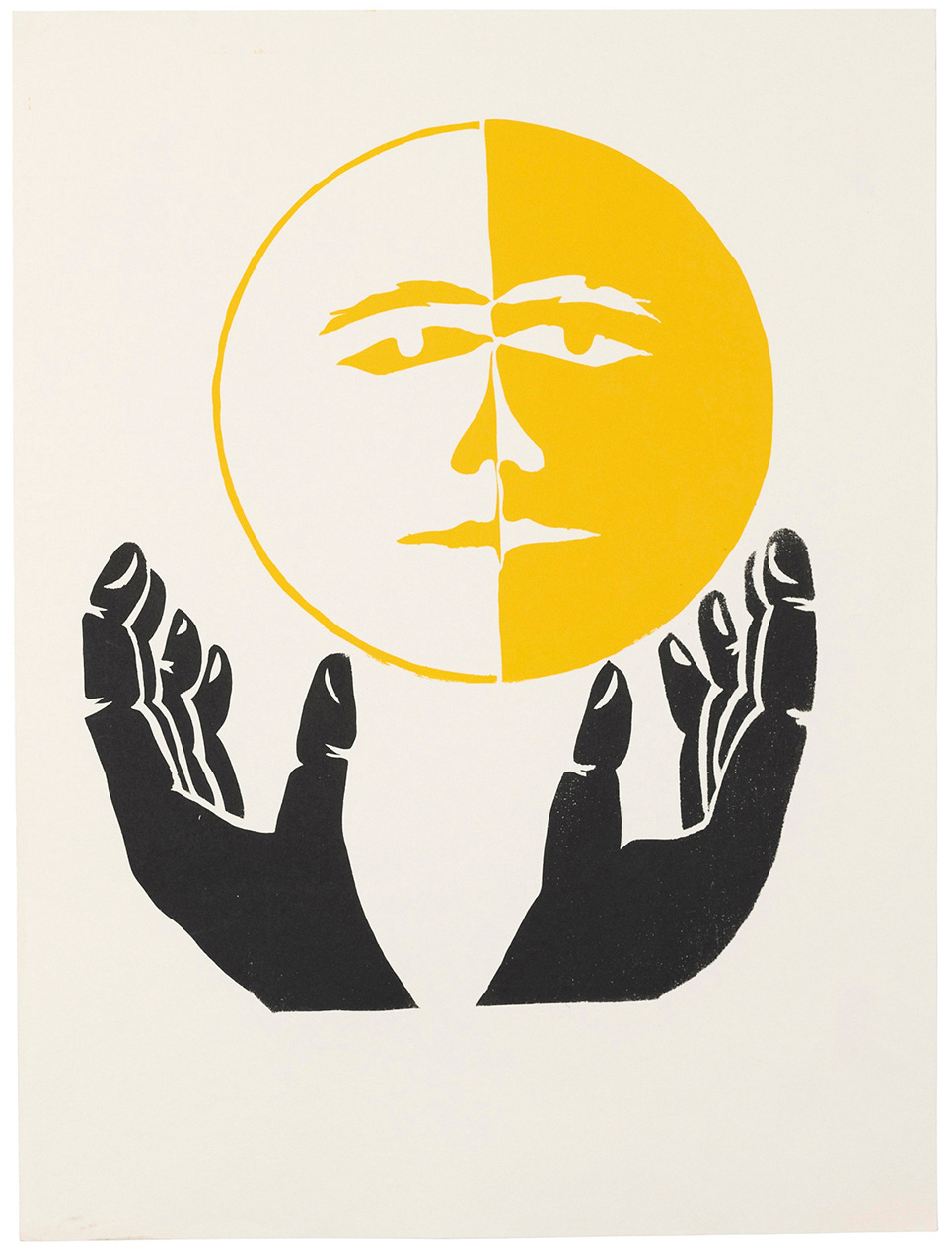

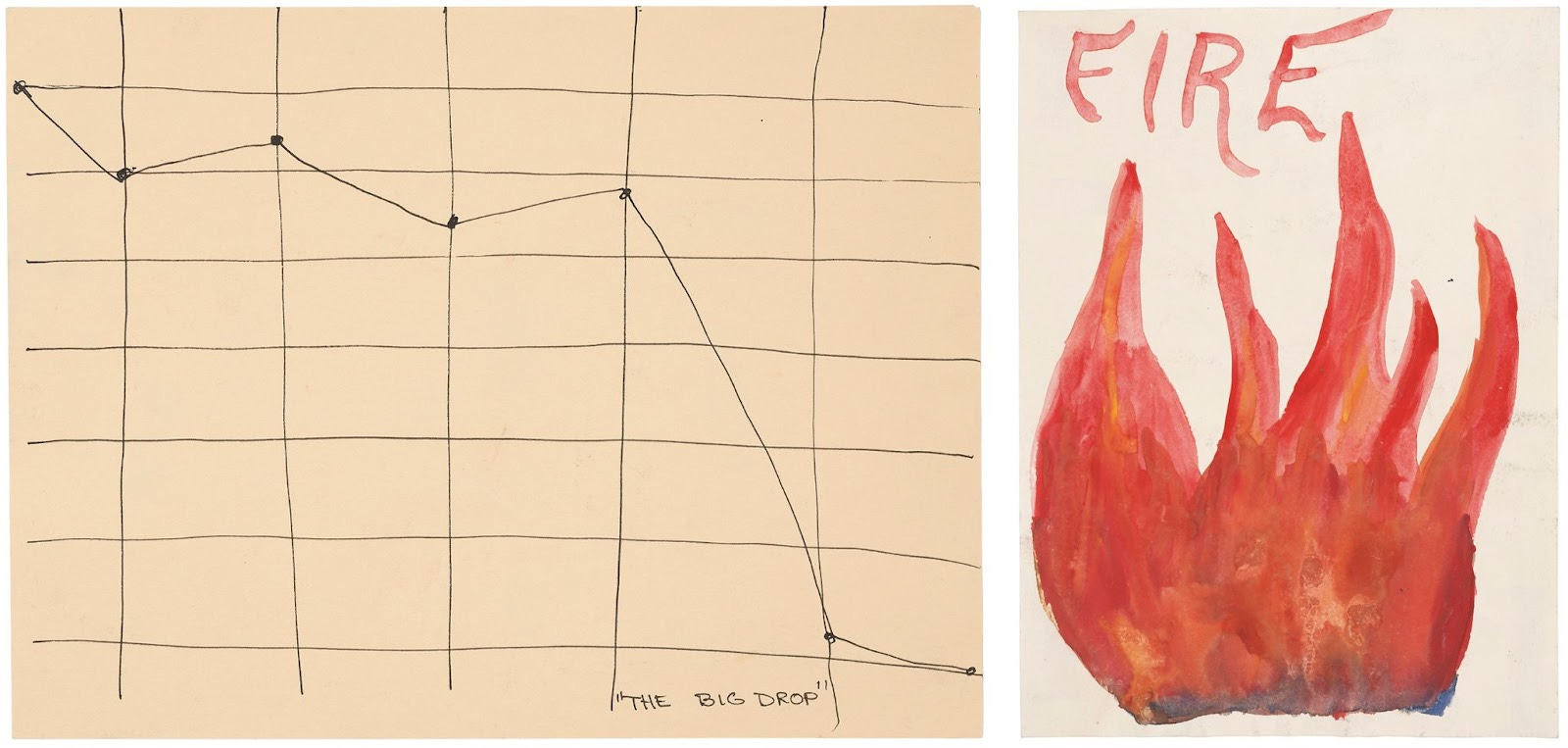

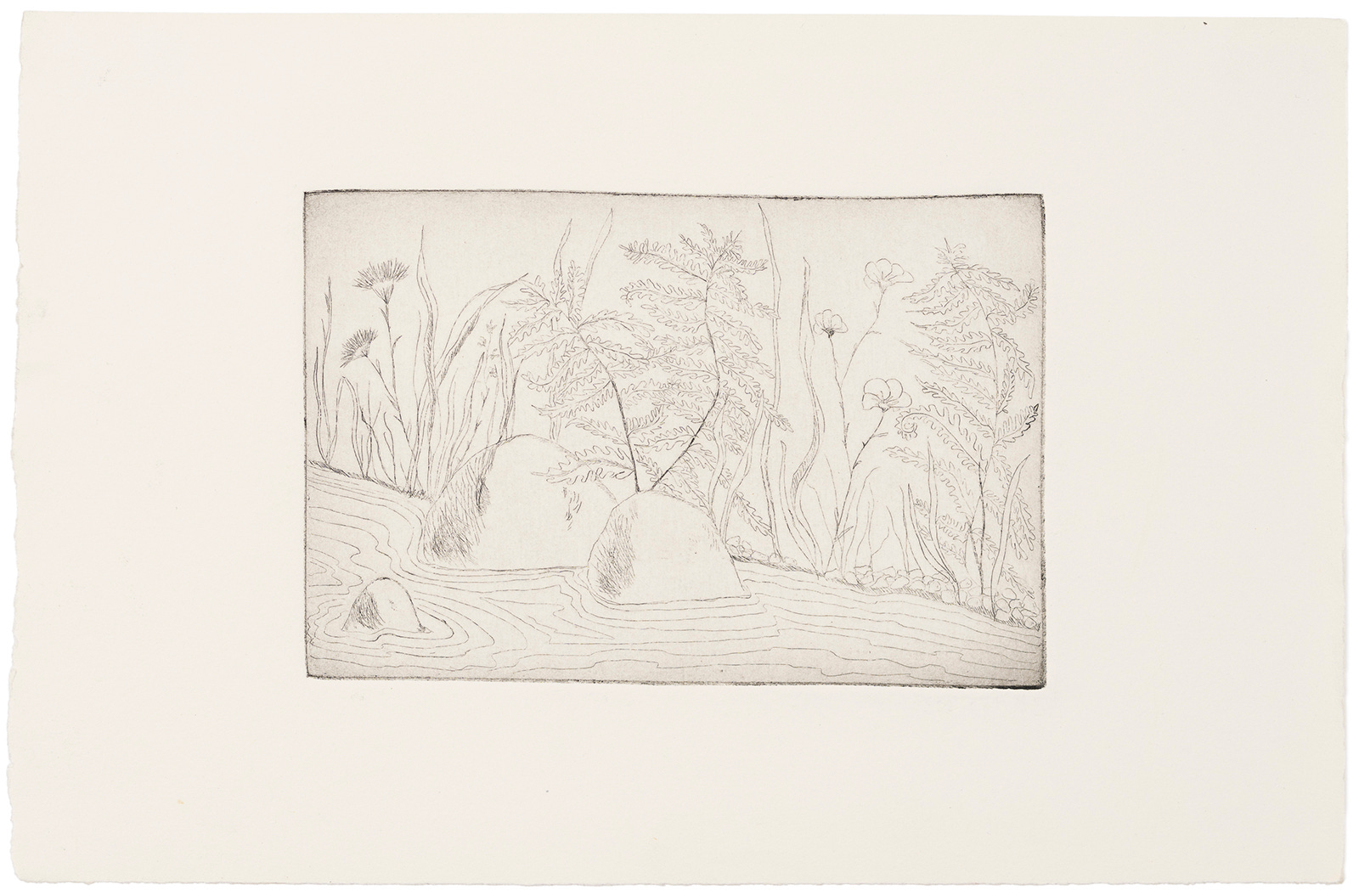

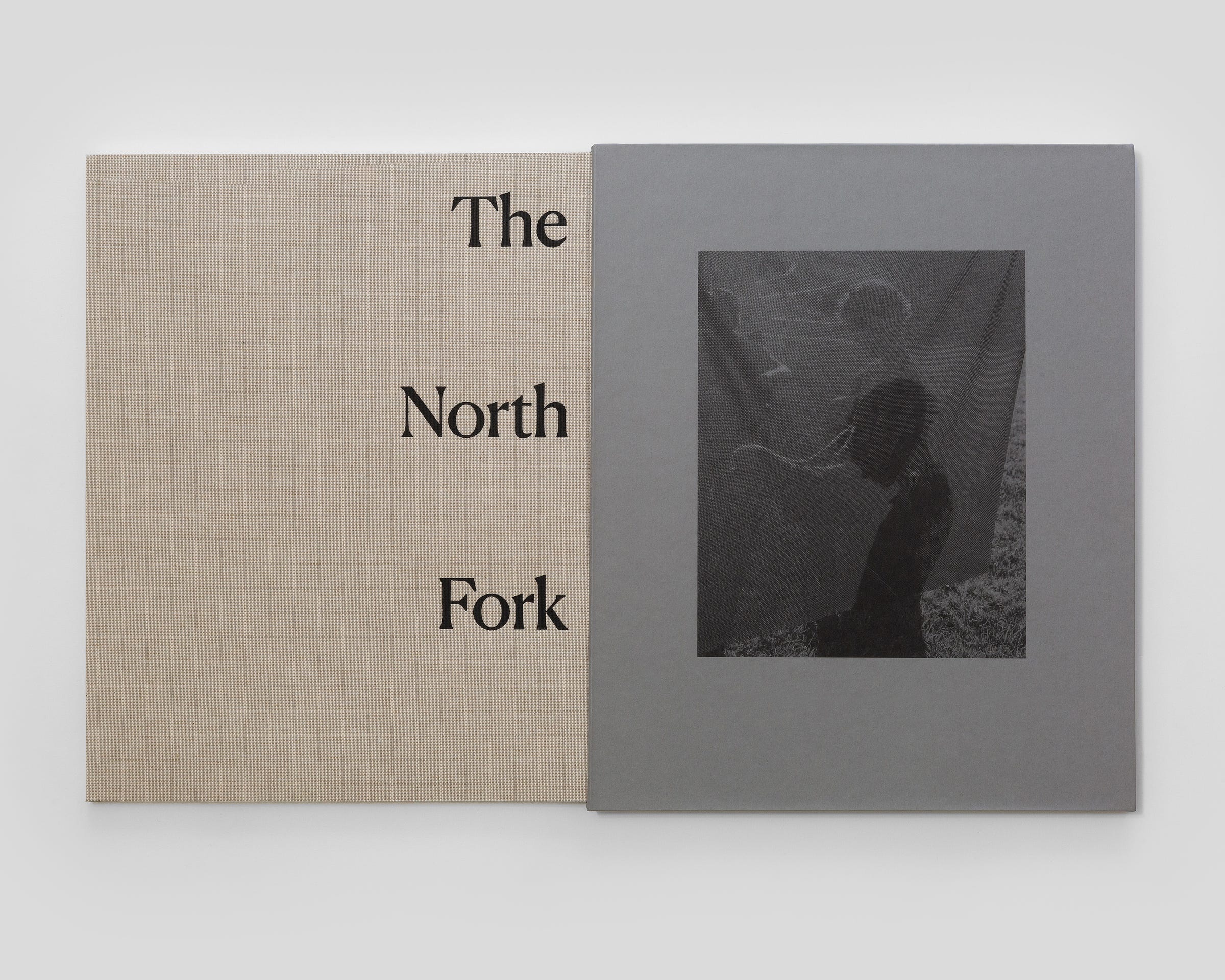

Do you have a particular approach to imagemaking? What’s your style? My approach varies depending on my care for and curiosity about whatever I’m photographing. My first project, The North Fork, was more stylistically constrained than my recent work. That entire project was shot in color, medium format, and one location — a rural river valley on Colorado’s Western Slope. Lately, I’ve been working with a variety of cameras, including medium — and large-format cameras and a 35mm point-and-shoot. I’ve been photographing in color and black-and-white at home and in various locations, from Colorado to Iowa and upstate New York. My current style is consistent with my earlier work, even if this expanded set of tools, subjects, and environments has broadened my output. Are you working on any projects at the moment? I’ve recently started a new one here in Colorado, and I’m in the final stages of my second long-term project, Son Pictures. This work has been my way of confronting notions of memory and family contextualized by my lifelong grief, my family’s collective trauma, and the permanent aftereffects of United Airlines Flight 232, which crashed on July 19, 1989, in Sioux City, Iowa, while carrying my mother and 111 others, who died, and my two brothers and 182 others, who survived. I started this project in 2016 by taking a trip from Denver to the crash site in Iowa, which is a story unto itself. Over the years, this project has changed as I have, especially since I became a father in 2019. My wife, Emma, and I now have two kids, and we’re very much in the thick of early parenthood. With Son Pictures, I’ve been interested in flipping the script on how my family’s story was portrayed in the news. After all, mass media was the leading culprit that broadcasted and sensationalized the crash. Were it not for the reportage in newspapers and magazines — and a Hollywood movie’s reenactment of Flight 232 and its aftermath — I’d have no memory bank of these incredibly heart-rending images nor any playback of them. Because certain editorial decisions were made to shock, spur newsstand sales, and get views, it only amplified the disaster. My dad shielded me from the media frenzy as best he could, but in the end, it was the barrage of widely distributed pictures — both still and moving — that influenced how I, as a young child, first came to see my mom’s tragic death. There were certainly heroic, life-affirming moments that were depicted, too, such as Gary Anderson’s iconic picture of Colonel Dennis Nielsen, a U.S. Air National Guardsman, carrying my twin out of the wreckage. Even still, that indelible image has been impossible for me to shake. Despite the downsides of such devastating imagery, I’ve found revisiting and scrutinizing Flight 232 pictures fairly edifying. Some years ago, I was given unique access to the remarkable archive at the Sioux City Journal, which holds a binder of negatives by three of the Journal’s former staff photographers, press prints, and other ephemera. As I see it, these documents represent the last minutes, seconds even, of my mom’s life. These are documents in which my brothers appear critically injured, evidencing the traumatic event they lived through. I’ve mainly been using Son Pictures as an excuse to be exhaustive and unabashedly obsessive as a family archivist and documentarian. I’m not just taking pictures but also collating many different sources into a decades-long chronicle that will be preserved for generations to come. How do you stay inspired? I rely on rituals that ground and humble me: walking my dog, prioritizing days with those I love, tending to my family’s garden, adapting to the seasons, and finding wonder and solace wherever possible. As much as I struggle to do so, putting down my phone helps. When I lived in the Bay Area, I was part of a group that started as four photographers and grew to around ten regulars who met monthly at Janet Delaney’s studio and home in Berkeley. We’d gather to eat pizza and share work-in-progress. I always came away from those nights questioning my ideas and inspired to make new work. I don’t know of a group like that here in Colorado, so I’ve taken to online video calls, which are somewhat sufficient but not comparable. Tell us about an artist who has intrigued you recently. For the past five years, I’ve spent more time with my mom’s art than with any other artist. She was never an exhibiting artist except for maybe some shows in college. I suspect if she were a living artist today, she would go by her full name, Frances Lockwood Bailey, or perhaps just Francie Bailey. Her archive of works on paper includes ink drawings, watercolor paintings, etchings, and screen prints from the 1960s and ‘70s. Ever since I decided to look closely at her art, it has intrigued me. Her archive is a breadcrumb trail, full of clues and visual cues for me to follow. Looking at her work has helped me find lineages between her works and mine. The imagery she created has also provided me with a basis for visually communicating with her, strengthening our limited mother-son bond. Perhaps most strikingly, she made several drawings and paintings as a young girl that seem to be premonitions of her death. Those early works make it easy for me to imagine her as an oracle. Ferns are a notably recurring subject in her work. Looking at Untitled (Fern Study #2), 1972, I’m struck by how the plants grow solely along the riverbank's edge. The river’s current is shown as a set of contiguous and concentric lines reminiscent of how mapmakers draw topography. The background is left blank — a terra incognita. My mom’s etching represents the essential riparian relationship between land and river, a relationship that’s part of the inner geography of many of us Westerners who have lived in a semi-arid, drought-prone climate. Her image also brings to mind fellow Colorado photographer Robert Adams and his book Along Some Rivers and this favorite quote of his by the poet Czeslaw Milosz:

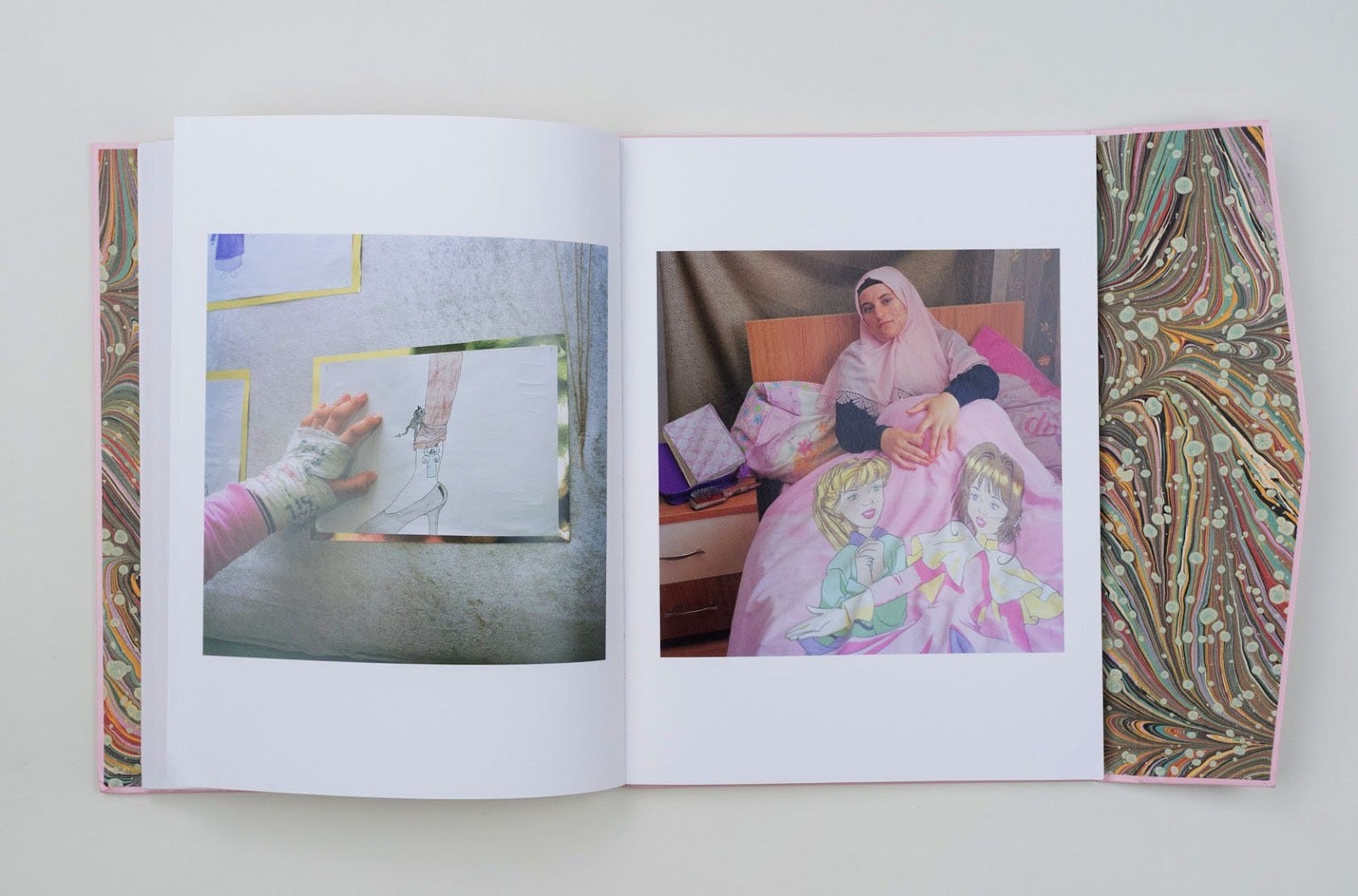

Show us a picture that moved you recently. Tell us about it. I recently had a virtual studio visit with the photographer Linda Moses. She and I initially met when she interviewed me four years ago. She uses her photography to decipher her family’s past and present. I relate to her interest in the construction of memory and how photography plays a significant role in how we remember the past. There’s also a sense of stillness and the seasons in her photographs that I’m struck by. Moses’ most recent work is taking on the idea of inheritance — be it objects, ideologies, or secrets — and she’s seeing what can be exposed through photography. I was moved when she shared a recent picture titled Garden Stool (Objects of Another House), 2024. In some ways, this is a simple picture of a family heirloom: a porcelain vessel Moses’ grandfather, a military man, brought home from one of his missions abroad. In another sense, it’s a continuation of her ongoing collaboration with her parents. In this case, her mom is acting as a supportive backdrop, standing with her hands held high. You can see spring blooms in the garden, which mark a specific moment in time and make this “timeless” object in the center of the frame a little less timeless. The improvised backyard studio environment makes the stool more personal and less precious. Moses’ framing and her decision not to photograph this heirloom in a perfectly lit, dust-free environment make this picture successful. I see it as a form of protest against the polish of commercial photography and the pillaging of other cultures. It's a picture that begs the question: What does it mean to inherit an object of war? And how do we, in America, define and glorify objects of war? Structurally, Moses’ picture instantly reminded me of one of my all-time favorite Henry Wessel photographs: Do you like music? What have you been listening to lately? Yes, I like all kinds of music. I grew up playing bass guitar and learned how to play alongside my identical twin, Spencer, on the drums, so I’m partial to music with a rhythm section that stays in the pocket and holds it down, such as The Meters or Khruangbin. My first favorite band was the Grateful Dead, and they’ll forever be on rotation. In the mid-'90s, my brothers and I would blast bands like The Smashing Pumpkins, Beck, Pearl Jam, Radiohead, and Nirvana, usually while playing street hockey in our driveway. Anytime I wish to conjure up boyhood nostalgia, that sort of '90s rock does the trick. Lately, I can’t get enough of Adrianne Lenker, both solo and with Big Thief. I collect photography books. Can you recommend a photobook that you love? I recommend Thomas Locke Hobbs’ Rampitas, recently published by The Eriskay Connection. It’s an impactful typology of self-made concrete motorcycle ramps throughout Medellín, Colombia. The ramps are utilitarian, but as Hobbs’ photographs attest, they’re also art. It's a prime example of a photobook in which the book's physical form and the pictures' content simultaneously reinforce each other. What I mean by that is that when you unfurl Rampitas, its accordion-style pages resemble the angular, ribbed, and stepped streetscapes of Hobbs’ black-and-white photographs. Another photobook I love, in which the pictures and book design are harmonious, is Sabiha Çimen’s Hafiz, published by Red Hook Editions in 2022. Have you read any good books? I recently read Little Failure by Gary Shtyengart and All Fours by Miranda July. The first is a memoir, and the second is a novel told from the perspective of a main character who somewhat resembles the author herself. I’d recommend both books for their surprising storylines and dark humor, which are enriched by age - and gender-specific growing pains and desires. Finally, show us something cool not related to photography. Surprise us! I’d like to show you this genre-bending poem titled “ ... a ship crashes down ... ” by Douglas Kearney, published in March 2020, which repurposes newspaper clippings and snippets of other found visual materials (such as concert posters and comics) and uses them as its syntax. Media, in this case, becomes shrapnel. Considering the tragedy my family endured and everything I’ve been working on with Son Pictures, I’m uniquely moved by Kearney’s use of disparate fragments and intimations collaged to form a devastating skyscape.

About the artist Trent Davis Bailey (b. 1985, Denver, Colorado) has been recognized for his long-term projects emphasizing the interrelationship of images and memory. His work to date has used photography and archives as tools for piecing together maps of complicated personal terrain — navigating internally complex places both past and present — to establish new points of connection. Bailey’s work has been shown widely in the U.S. and abroad and is held in the permanent collections of the Denver Art Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Photography (MoCP) in Chicago. He has received numerous awards, including a 2024 Working Assumptions Project Grant, a 2019 Film Photo Award, the 2015 Snider Prize from the MoCP, and a 2014 Magnum Foundation grant. His first monograph, The North Fork, was published by Trespasser in the fall of 2023. He was an artist-in-residence at Brooklyn Darkroom in 2023 and Anderson Ranch Arts Center in 2016. His photographs have been regularly published in periodicals such as The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, ProPublica, T: The New York Times Style Magazine, and SSAW. Bailey received his MFA from the California College of the Arts and his BFA and BA from the University of Colorado Boulder. He has taught at numerous institutions, including the California College of the Arts and the College of Arts and Media at the University of Colorado Denver. He is working on his second monograph, Son Pictures, which will be published in 2026. Trent is based in Evergreen, Colorado. Follow him on Instagram @trentdavisbailey. One more thing… I think it’s sold out, but Trent’s book, The North Fork, published by Trespasser in 2023, is remarkable. You can see these images on his website. If you can, find a copy. Thanks again for working with me on this, Trent. Happy holidays, everyone! I would love for more folks to hear about FlakPhoto. Word of mouth is how this spreads, and every little bit helps. Please tell your friends! |

Show & Tell: Trent Davis Bailey

11:42 |

Assinar:

Postar comentários (Atom)

0 comentários:

Postar um comentário