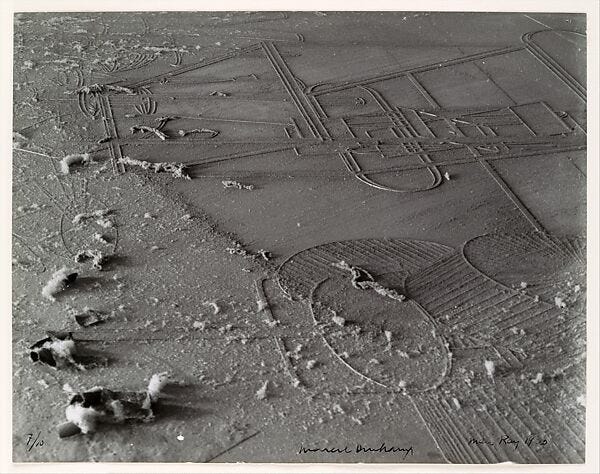

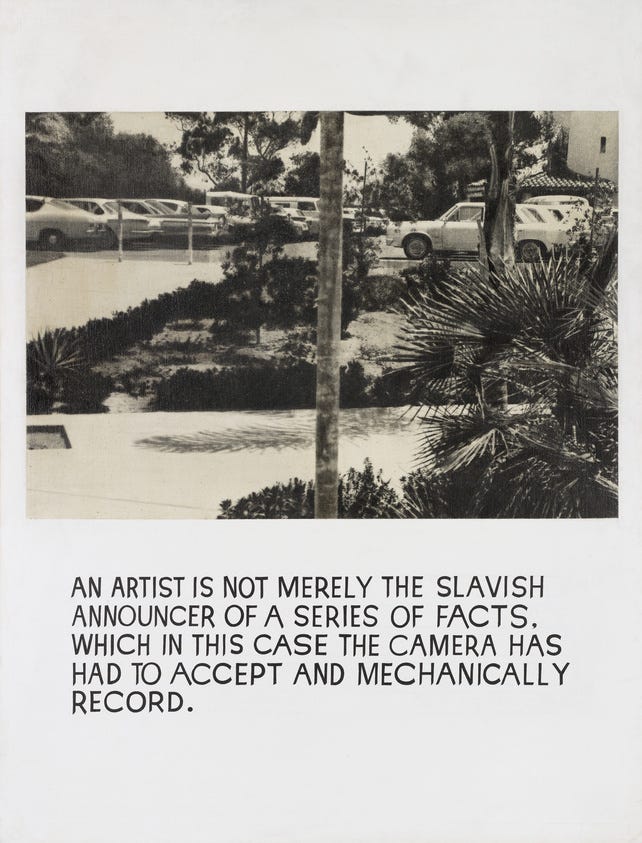

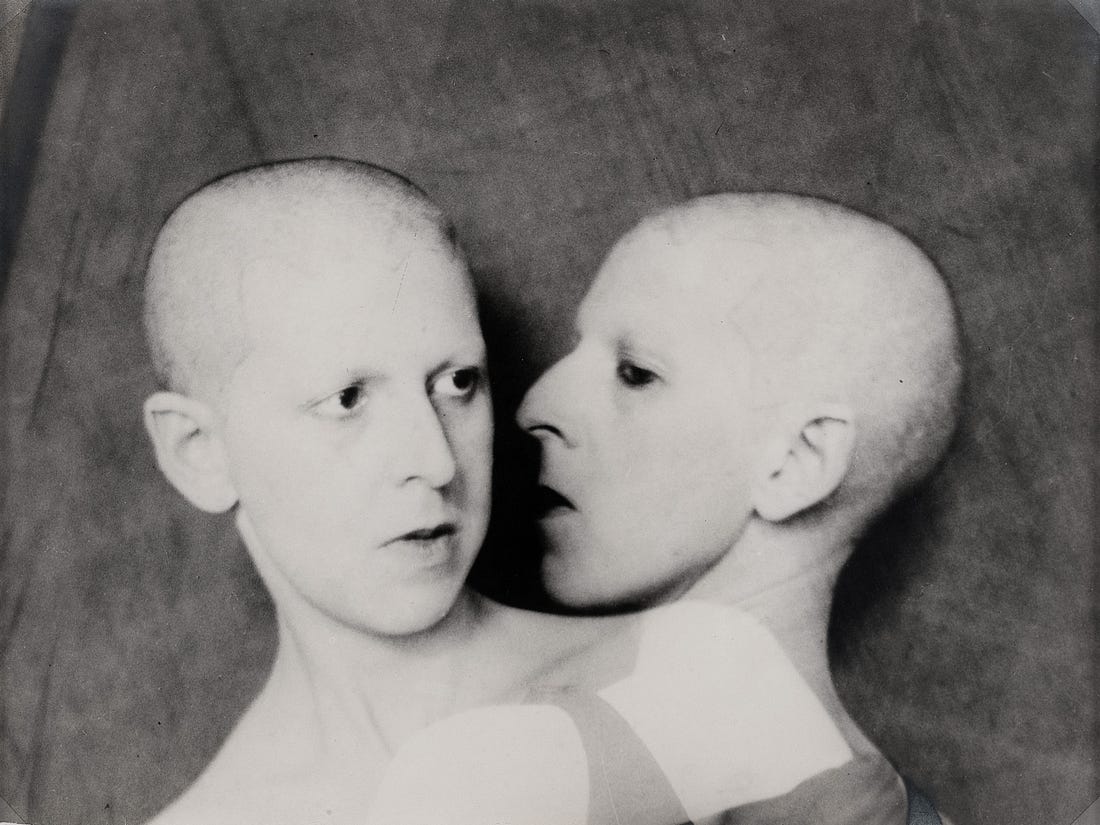

A Conversation with David Campany"A creative life is a life that doesn’t fit - it is resistant, searching, unsatisfied."Last autumn, David Campany was invited to appear on a podcast. The conversation was to take the form of a panel discussion on the relationship between image makers and the photography industry. During the recording, the host asked how image makers should present themselves and their work, and two of the panellists “immediately started offering hyper-professional advice. Exactly what format a portfolio should take. Exactly how a statement should be written. Exactly how to talk about your work and even how to photograph yourself,” as Campany described in a widely-shared Instagram post afterwards. He was “a little horrified,” and told them so. “To me it seems extremely dangerous, and extremely lazy, to prescribe how people should present,” he wrote. It feels increasingly as though the quality most desired in the artistic product — and it does often feel like a product — is palatability: work that is as available and consumable as possible, which means not only that the images themselves should be immediate and satisfying and easily read, but also that they should be packaged and prepared in a delectable way (when they are sent out to curators, editors, and so on). The artist themselves becomes part of the package. I was thinking about this when I came upon these lines by Marguerite Duras, quoted by Deborah Levy in Real Estate:

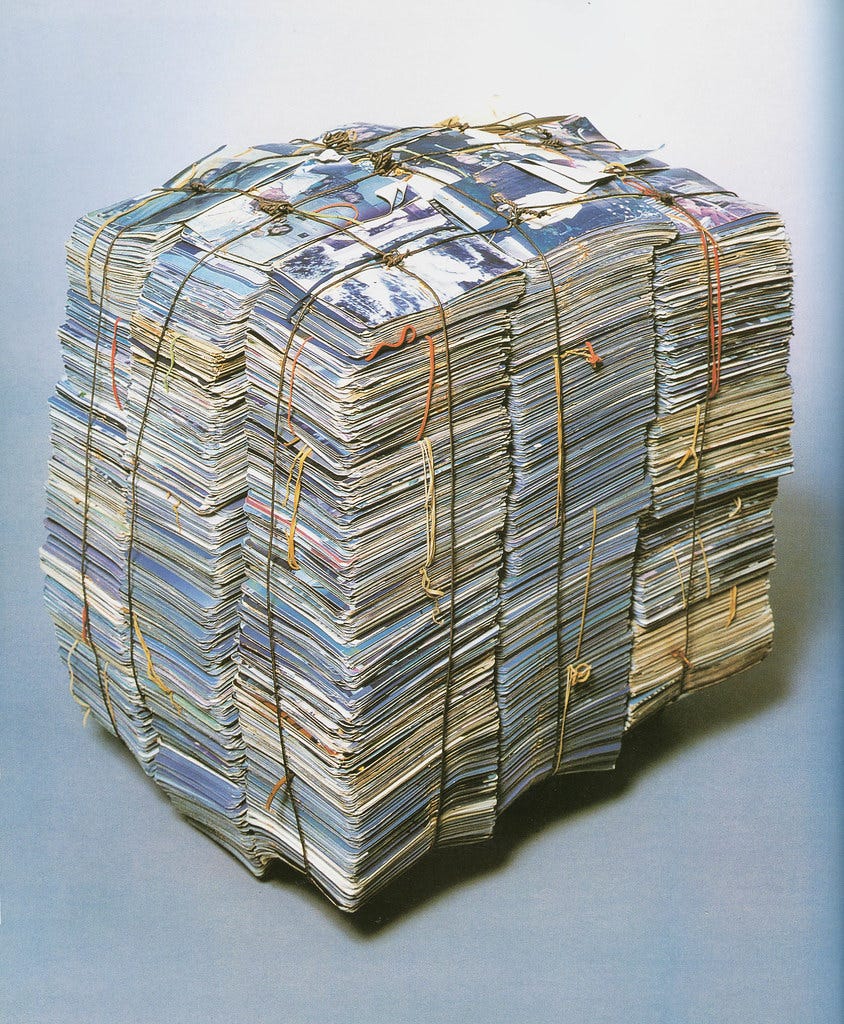

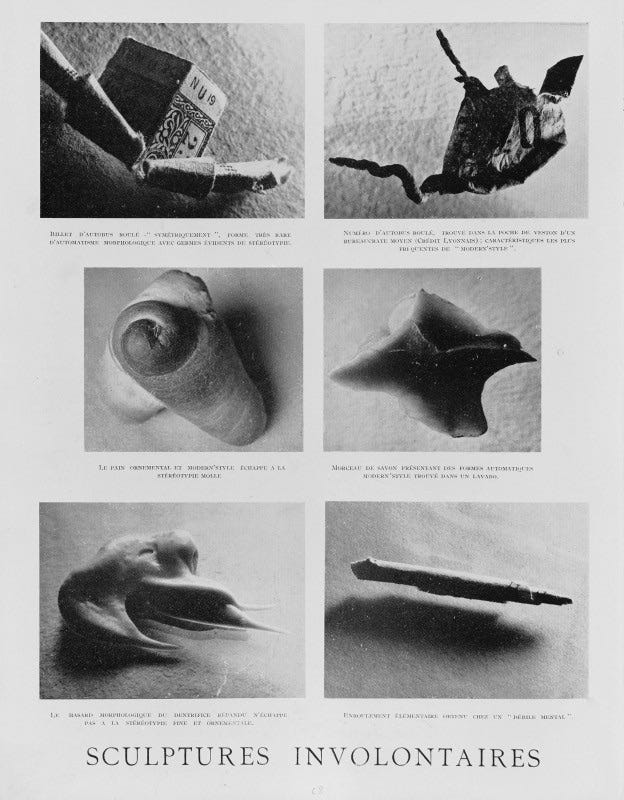

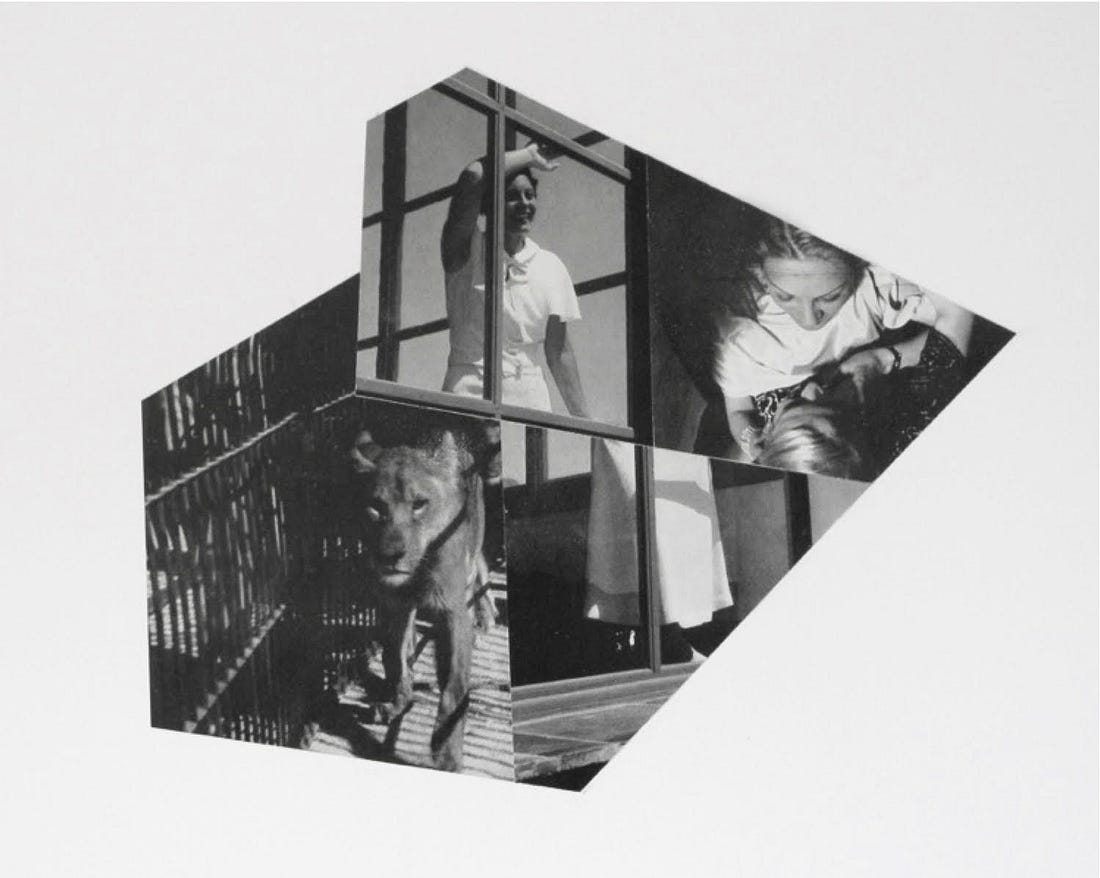

It made me think about photography, and the predicament of the photographer/artist. More and more it feels like the freedom Duras writes of — and the uncomfortable chaos or opacity that such freedom implies — is inadvisable for the contemporary photographer too, or at least the photographer that would like to make any kind of a living from their work. The cost of the widespread appetite for clearness and regularity, for frictionlessness, for charm, is that eventually artists begin to blur together into one undifferentiated mass, churning out images that feel more often like advertising than meaningful works of art. We are losing authorship, and becoming our own cops. Perhaps part of the role of the curator today is to shoulder some of the fear of the freedoms and frictions of open space; of risk-taking; of focussing more on the ideas themselves than on smooth and intelligible surfaces. I am grateful that Campany’s work as a curator (he has just been appointed director of the International Center of Photography), as well as a writer and artist, defends the virtues of difficulty and freedom by its example. This includes the freedom of the work, and indeed the artist, to be strange or silent, to resist the imperative of fast and frictionless understanding. When I saw his post at the end of last year, I wrote to him to ask about some of these things. Alice Zoo: I first wrote to you in October after reading your Instagram post about your experience appearing as a guest on a (never-published) podcast. It seems to me that the horror you described was produced by the ways that the conversation didn’t even pretend to aspire to the ideals of art — like experimentalism, innovation, strangeness — but rather instead to the ways that artists should smooth themselves and their work into products to be more easily sold, distributed, digested and consumed. You spoke, in your post, about the dangers of conformity. I’ve been thinking, since then, about the idea of genuine creative freedom, and the ambiguity and even chaos that can imply, and whether there’s space for it in the marketised version of industry art-making that these kinds of podcasts and articles encourage. Is freedom a principle that is important in your work, and the work you’re drawn towards? David Campany: Freedoms are always relative, not absolute, and clearly economics play their part. I think it was Roland Barthes who said the purest condition is that of the amateur, the lover of things, the one who does things for the love of it (in French the root connection to love, amour, is clearer than it is in the English use of the word). The amateur does not, or will not, or need not, place what they do under economic pressures. They either earn their money elsewhere or have access to money somehow. Beyond this, living a creative life is always going to be a series of challenges. I think my horror at having to listen to over-professionalized advice from ‘industry’ people is related to the way ‘creative’ has become a noun. As if there are people we can call ‘creatives’. This to me sounds nauseatingly close to ‘content provider’, someone who works in the ‘creative industries’. I think this completely misunderstands (or actively refuses to see) how a creative life is a life that doesn’t fit, on some profoundly important level. It is beyond the given paradigms. It is resistant, searching, unsatisfied. I don’t want to romanticise the creative life but at the same time it’s not helpful to reduce it to professionalism or suitability to the economies of culture. The other week I had dinner with an artist acquaintance who I have helped for a long time. She has recently learned how to ‘art world’ after years of struggle, and she’s going for it 150%. It’s kind of hilarious and creepy to watch the swing from disgust at a world that didn’t want her to total embrace of it because it has embraced her. Doors are opening. Opportunities. The seduction of money, the world of ‘high profile friends’ as she called them, quite unironically. She’s suddenly arrogant and self-important, and fake humble, in ways she doesn’t quite realise are annoying everyone. But it’s totally understandable. At the same time, another artist acquaintance makes work at least as good, doing it all in her spare time around her day job in a factory. She longs for something better, of course she does, but for now that longing is poured into her work, whenever she can make it. These cases are real extremes but we do live in extreme times, and I wish we didn’t. AZ: I wonder, too, if part of the problem with the professionalisation discourse is that it shifts the burden of proof onto the individual artist — here’s how you can streamline yourself, and so on — rather than asking more fundamental questions about larger, perhaps more intractable problems, such as the fact that the UK government has progressively deprioritised the arts, defunding cultural organisations and destroying humanities departments at schools and universities. It seems to mirror the way that conversations around, say, health, or climate, are so often pointed at the individual rather than the corporations and structures that make it harder and harder to exist in the given paradigm. I’ve long wanted to write a newsletter about day jobs, and the ways that the artists I know support themselves. I feel angry that even longevity and acclaim in the industry often don’t translate to a living wage. I’m saddened to think of all the work that never got made because the artist had to quit. I know brilliant artists, ones who have won the prestigious prizes and have been fully embraced by the institutions, who are on universal credit. I wonder what kind of refusal is genuinely possible within the structures and systems available if, say, a person doesn’t come from a well-off family, or have a partner with a stable job, or is a single parent. The system as it is anoints a few chosen ones, like the acquaintance you mention, and the rest are left fighting over scraps. Anecdotally it seems that, for all the noise about diversity and inclusion, it's mainly the same kinds of people getting the money as always have. Do you think there are many of these different kinds of conversations happening — ones that agitate against the structures rather than the individual, and think radically about how those structures might be changed? And in the meantime, how artists might support one another, and consider themselves part of a community or ecosystem? Do we have to accept the economies of culture as they are? DC: I’ve just been reading a book about the history of the NEA (the National Endowment for the Arts, a key funding body in the USA). When do you think NEA funding was at its height? It was under Nixon. Art culture had become politicised by the civil rights movement, by the new wave of feminism, and by the anti-Vietnam war movement. Someone in the Nixon government had a word in the president’s ear. ‘These artists will be less dangerous if we fund them.’ That’s a scary historical fact, from whichever angle you look at it. Yes, there’s lots of talk and some action around getting together to form communities and art ecosystems within the larger economy. There are lots of ways to share costs of living, and share the burden of precarity. But that’s not specific to artists. That’s the history of communes and communal living under capitalism. It doesn’t work if those in the commune are all artists or all artists all of the time. You need farmers, builders, plumbers and all the rest. So it’s not a matter of ‘artists’ sticking together, so much as people wanting to live communally sticking together, and there is art in that wanting. I saw a clip of Jeremy Deller being interviewed the other day. He was pointing out how often rich collectors talk about artists being visionaries who can change the world, when in fact it’s they, the rich, who can change the world. Instead they buy art tell themselves they’re supporting change. As Terry Eagleton once put it, ‘the only thing the bourgeoisie won’t hang on its walls is its own political defeat’. My interest has always been photography, and an important part of the reason for this is the many different ways it fits into culture and the economy. If you’re a painter or a sculptor, pretty much your only context is art. Photography’s scope and field of operation is much wider, although it’s no less precarious, especially when everyone has a camera in their pocket and AI threatens to usurp. But again, I don’t think photographers banding together is much of an answer. It’s people that have to band together. A community, an ecosystem, takes all sorts. AZ: Last year I read your book-length conversation with Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, Indeterminacy, in which you wrote that “Arguably, ambitious culture, important culture, is grounded in the refusal of the fixed terms on offer in favour of keeping the door open to complexity, provisionality, possibility.” It’s interesting that a refusal of your own (in the context of the podcast) resonated so widely — that your post about it on Instagram went semi-viral, and attracted far more kinds of people than would usually engage with your posts. It seems this is often the way: that a public refusal generates a huge public response, as though everyone is waiting for somebody to show them how. It seems like there’s more of an appetite for complexity than is generally accepted. And then for artists, it seems often that when the right or usual way of doing things is given up on, significant new freedoms are possible, and new ground can be broken. There are many examples of this, but for some reason today Knausgaard comes to mind. He was frustrated, blocked and desperate, and so decided to abandon literary convention and just write everything down, in a project that would become a kind of death — to “empty every reservoir so there would be nothing left” — and the result was the six-part My Struggle, which he wrote extremely fast and which was received by many as a masterpiece. Are there particular examples of creative refusal, contemporary or canonical, that feel important or totemic for you, that have made something possible in your own work? DC: Being non-canonical in my approach to photography is so central, and feels so natural to me that I wouldn’t even call it a refusal, although some do see it that way. I’ve found the idea of a canon quite absurd, particularly in photography, a medium so dispersed across society. I prefer to follow the image, not the names, not the money, not the received wisdom about what’s important. I remember writing my first book, Art and Photography, a survey of the places of photography in art since the 1960s. I didn’t select on the basis of names, I chose images, which meant there are some big names that aren’t in the book and lots of lesser known names that are. In the exhibitions I curate, a postcard or a magazine spread might be placed next to an expensive print by a canonical artist. I don’t do this to elevate the postcard or magazine spread, nor to bring down the canonical work. It’s simply a result of being interested in images, and wanting to encourage others to do the same. But I would stress that I’m non- or a-canonical, rather an anti-canonical, which is why ‘refusal’ may not be quite the right word for it. Something that does feel more like refusal for me is the wish to keep the spotlight firmly on the work I do. I avoid being photographed as much as I can although it’s not always possible. I do worry that the arts in general are becoming conditioned by appearance, by a certain conformist presentability. This conformist presentability might personalise the arts but it’s detrimental in the long run, not least because it excludes those who are reluctant to step into the given frame of visibility. I’m well aware that a lot of great work — art making, writing, curating — is done by those who would prefer to remain off-stage, so to speak. As I write this, I wonder if my thoughts are connected with my not really wanting to know about the lives of makers. I prefer the imaginary construction of the maker that naturally comes with an individual engagement with the work itself. When I read Virginia Woolf’s writings, I make for myself a ‘Virginia Woolf’ in my head, inevitably, but this is unlikely to be the same as the actual Virginia Woolf. I wonder too if something of this desire to escape the tyranny or the cult of the maker is why there is such a lot of interest in vernacular ages, found images and so forth. Without a name attached, the viewer can feel much more free in their response. AZ: It makes sense to me that attaching too strong a personality to a given work would limit its freedoms — that it would make it harder for a work to be surprising or subversive. I have a friend who, new to his second language, decided to read Pedro Páramo in the original Spanish, very slowly, dictionary in hand. After he was finished he read it again in translation, and found that the version he'd imagined from his cobbled-together text and misunderstandings was more interesting than the story as it was intended — it was stranger. I wonder if attaching a work so neatly to its maker is something like reading a work in translation, perhaps making it more intelligible but less interesting, shutting down some of the ambiguity that might allow us a deeper, odder engagement with it, and so bringing our own thinking to new and unexpected places. I feel like Instagram, where this conversation began, has a large hand in this conditioning by appearance: it places the emphasis on the person rather than the work, on building a following. As far as the images themselves are concerned, the algorithm prioritises the crowd-stopping single image rather than the body of work, or the sequence, or the strange or subtle or ‘wrong’ image. I’m often thinking of something Teju Cole wrote there — choosing between two images, he opts for the worse one. “Intransigence is what interests me,” he said. It also seems as though the emphasis on appearance and presentability goes beyond just personalising the arts, making them more palatable, but is even coming to be a necessary part of the sales package. There has been conversation recently about the increasing emphasis on identity in art — this piece in Harper’s, for example, and then Martin Herbert's (who incidentally wrote a great book about artists' refusal to cooperate with the mechanisms of the art industry) response to it in ArtReview — and in my own anecdotal experience, as a reviewer at portfolio review days and so on, it feels like the self is more and more the preoccupation of young artists. I completely agree with what you say about photography, that interesting images come from everywhere, including from non-artists and vernacular sources — but in terms of the artist shows and books you’re seeing, have you noticed an increasing focus on work that concerns identity? Do you feel that artists are increasingly incentivised by the industry to put themselves and their contexts into their works? If so, what effect is that having? DC: About a decade ago I was involved in a project instigated by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, titled Alias. They asked about twenty artists and writers to each write the biography of an imaginary artist. Around 500 words. I invented a woman born in 1900. Among other things, she was bisexual, a kleptomaniac, and a collagist who fell in with the surrealists in 1920s/30s Paris. She died young when a jealous lover set fire to her house. I figured Broomberg and Chanarin were going to publish the biographies as a collection, but instead they asked us all to make the art our imaginary artist would have made. So I found myself trying to inhabit the persona of this artist I had invented, sourcing interwar Parisian magazines to cut up, and inventing a style of collage that could have existed but didn't. A few years later I included the collages in a public talk I was giving about what it means to be a writer, curator, historian, and artist. A young woman in the Q&A stood up and said she suspected the collages were the most autobiographical and personal thing I'd ever made. I was taken aback but she was dead right. Then she quoted that great Oscar Wilde line: Give a man a mask and he will tell you the truth. It's not always when we think we are making ‘diaristic’ or ‘confessional’ work that we are being ‘personal’ and ‘authentic’. Art culture, particularly photo art culture, has it all wrong. It didn't used to. It used to be well aware of this, but you’re right, a sort of karoake version of the personal is now dominant, if not in the work itself then in the way it gets narrated and attached to a personality. It’s pretty tedious, most of the time, and it will soon become clear just how related it is to the rise of social media and the anxieties that come with living in a visual culture of permanent reputation management. Speaking of surrealism and of Instagram, I posted recently about my favourite thing produced by the surrealists: the artists’ portraits from the publication that accompanied the New York exhibition ‘The First Papers of Surrealism’ in 1942. They couldn’t find photos of all the artists so Marcel Breton and Marcel Duchamp, the curator-editors, appropriated portraits from various books and magazines. The choice of images was not random. Sometimes there’s a resemblance, sometimes there’s another kind of connection. Walker Evans’ photo of the sharecropper Allie Mae Burroughs was used to represent the painter Leonora Carrington. Picasso is represented by two people looking in different directions — a nod to Cubism’s multiple perspectives; Joan Mirò is represented by a man and a woman (I guess because in America ‘Joan’ would be read as a woman’s name); Duchamp chose for himself one of Ben Shahn’s photos of a woman farmer. She looks like Duchamp, who had long played with gender ambiguity. Who knows what the unsuspecting audience might have made of these ‘Compensation Portraits’, as they were called. Kind of refreshing in our era of endless promotional (self)portraits. I was recently in the Toronto studio of the photographer Edward Burtynsky. He is, pre-eminently, a photographer of the world ‘out there’. A mural-sized test print of his latest image was unrolled on a large table and then pinned to a magnetised wall for viewing. It was shot in October 2024 on a trip to the Democratic Republic of Congo. It is a wide, elevated view of the steep escarpment of an open industrial copper mine. That is what the large machinery, dwarfed by even larger landscape, is here to extract. To get to it, however, many metres of surface rock must be removed, and in this rock there are small but valuable traces of cobalt. With the exponential rise in the world’s numbers of smartphones and electric cars, cobalt has become one of the most in-demand substances on the global marketplace for natural resources. It is a vital component of rechargeable batteries. Thousands of artisanal miners, including women and children, work with simple tools and bare hands in this hostile landscape. They break the rock to get to the cobalt, which is toxic to the skin. Working conditions in such mines are among the most hazardous and poorly paid in the world. Moreover, the cobalt supply chain is of such complexity — with any number of intermediaries between those working in the mines and the companies that manufacture batteries — that there are currently no guarantees that it does not involve child labor and other illegal forms of exploitation. It is tempting, of course, to read this image of cobalt extraction, and Burtynsky’s work in general, as somewhat dispassionate, distanced and even cold. About as far from ‘personal photography’ as one could imagine. By extension it is tempting to see Burtynsky as more interested in humanity than humans, perhaps; or more interested in scale and statistics than anything that might feel intimate. But reach for your iPhone, so close to your body. Think about the cobalt that keeps it alive and ready for you whenever you need it, twenty-four hours a day. Think of how insidiously integrated it is into your life, both as a device, and in terms of the images you make with it, perhaps diaristic or confessional images. There is a line of connection that reaches all the way from your hand in your pocket to the countless hands in the earth of that hellish mine. It’s a cliché, of course, but what is local is global, and what is global is local. What is personal is political, and what is political is personal. The webs of interconnection are tangled and intangible, but they are also undeniable. There is no ‘personal’ realm beyond or separate from what Burtynsky’s imagery asks us to see. His photograph of that cobalt mine ought to feel as personal to you as your latest selfie. Perhaps it needs a shift in perspective to grasp this. AZ: That feels like a good place to end, but just before we do I want to alight briefly on the idea of surprise, which often comes up in your writing. What has surprised you lately? DC: I’m often surprised by the changes in my judgements, values, tastes and views. I like to revisit works of culture that have meant a lot to me. Certain novels, films, books of photos, buildings, pieces of music. It’s always a surprise to find that while they have not changed, I have, and sometimes quite dramatically. This can be a really illuminating measure of one’s own development. Every month I ask each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue. David Campany’s recommended reading: A Manual for Cleaning Women — Lucia Berlin Complete Stories — Clarice Lispector Poetics of Cinema — Raùl Ruiz A huge thanks to David Campany, and to you for reading. You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below: You’re currently a free subscriber to INTERLOPER. This is a reader-supported publication, and I’m so grateful for all paid subscriptions; they help me continue to work on this project. If you enjoy the newsletter, consider upgrading. If you’d like a paid subscription but can’t afford it, reply to this email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked. |

A Conversation with David Campany

04:02 |

Assinar:

Postar comentários (Atom)

0 comentários:

Postar um comentário