A Conversation with Keisha Scarville"I want to know: what are the things that trouble a photographer?"I first came across American artist Keisha Scarville’s work at her exhibition, Hot/Slow/Step, at Huxley Parlour in 2022; I have been preoccupied and compelled by it since, not least the book that she published with MACK the following year, lick of tongue, rub of finger, on soft wound. At Arles this year she showed Alma, an exploration of “the materiality of absence” that took the form of large photographs and objects made and collected following the loss of her mother; she also exhibited at Webber Gallery in LA this year, a show with the same name as her book. I long to find myself in a physical space surrounded by her images again. But the book. It opens with water, then stone — pages of this stone, close up, its patterns and textures rendered in the graphite black and white that is the overwhelming language of the book. And then, within the walls that now contain us here, images overlaid in collage, rippling, rhythmic: flesh, hands, fabrics, flames. The cosmos. Bodies crouched and ready to run. The images collected in the book are not only Scarville’s own, but also take in those from the archives she works with, both personal and public. It rewards the reader who returns to it again and again; while preparing for this conversation, throughout it, and even now as I look over the book once more, it kept shifting and changing for me, deepening, revealing new sense and patterning in the way that dreams do. Or perhaps in the way that weeks or years of dreams do — the new symbols arisen and approached from different angles, the surprising detail, the meaning you grasp for a moment before it slips away. It was a great pleasure to speak with Scarville via email and Zoom this summer, parts of which conversation are recorded here below. She is a practitioner invested in latency, and the value of opacity and resistance, as you’ll see; it may be interesting to read this newsletter alongside the one with David Campany, who shares this ethics. I’m so glad that work like hers exists, that it can chart a path for other artists today; it is ballast against the pressures to be immediate and legible. Not that the work itself is didactic in the slightest; already I find myself wary of unintentionally reducing this layered, tension-filled work — which stages and responds to so many things: thresholds, collective histories and imaginations, the many narratives of the Black diaspora — to some kind of straightforward read or meaning. Having to introduce it, as this format demands, cannot but fail. Really, I just recommend spending time with the book yourself. At one point I wondered if the freedoms Scarville found in making this work had made themselves felt elsewhere in her life — as artist, as educator, as person. “I feel that it doesn’t have to stop at the book,” she told me. “All of this,” — and here she gestured around herself — “can be the work too. And this can be the way in which the work lives, and becomes.”

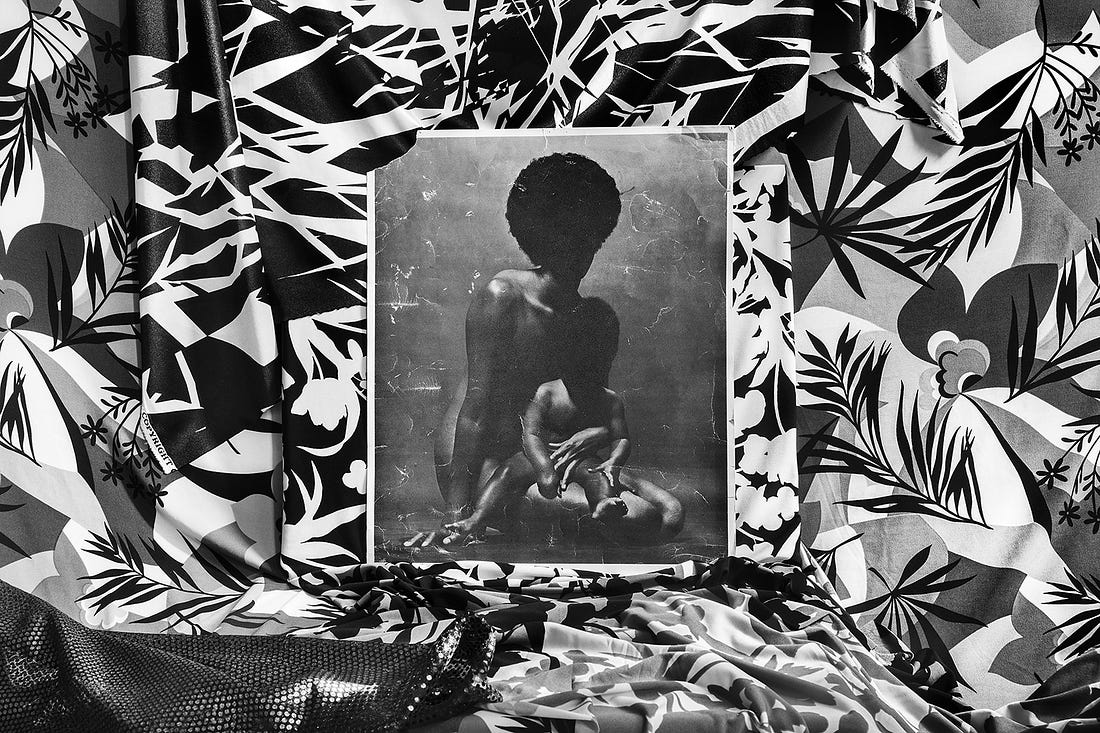

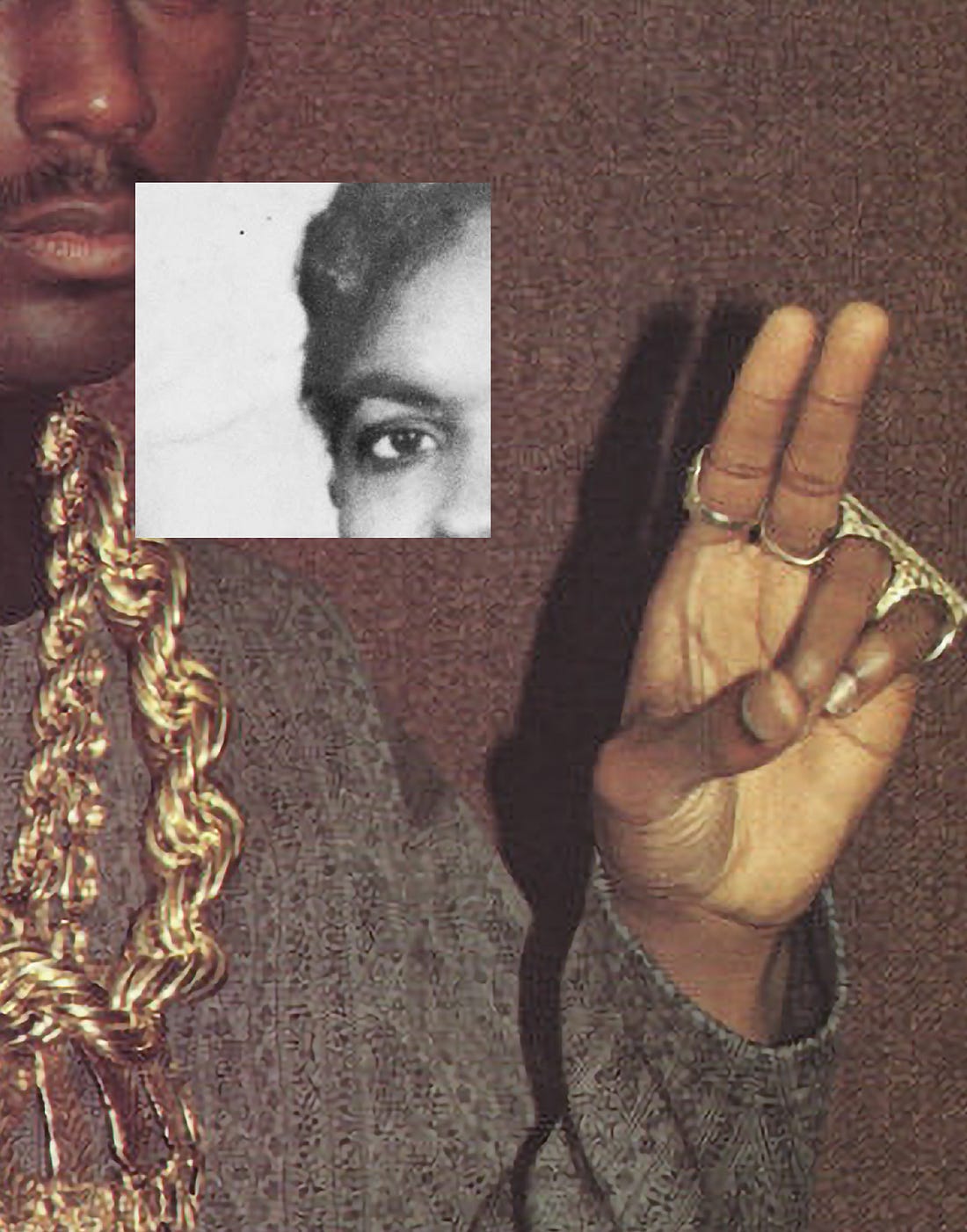

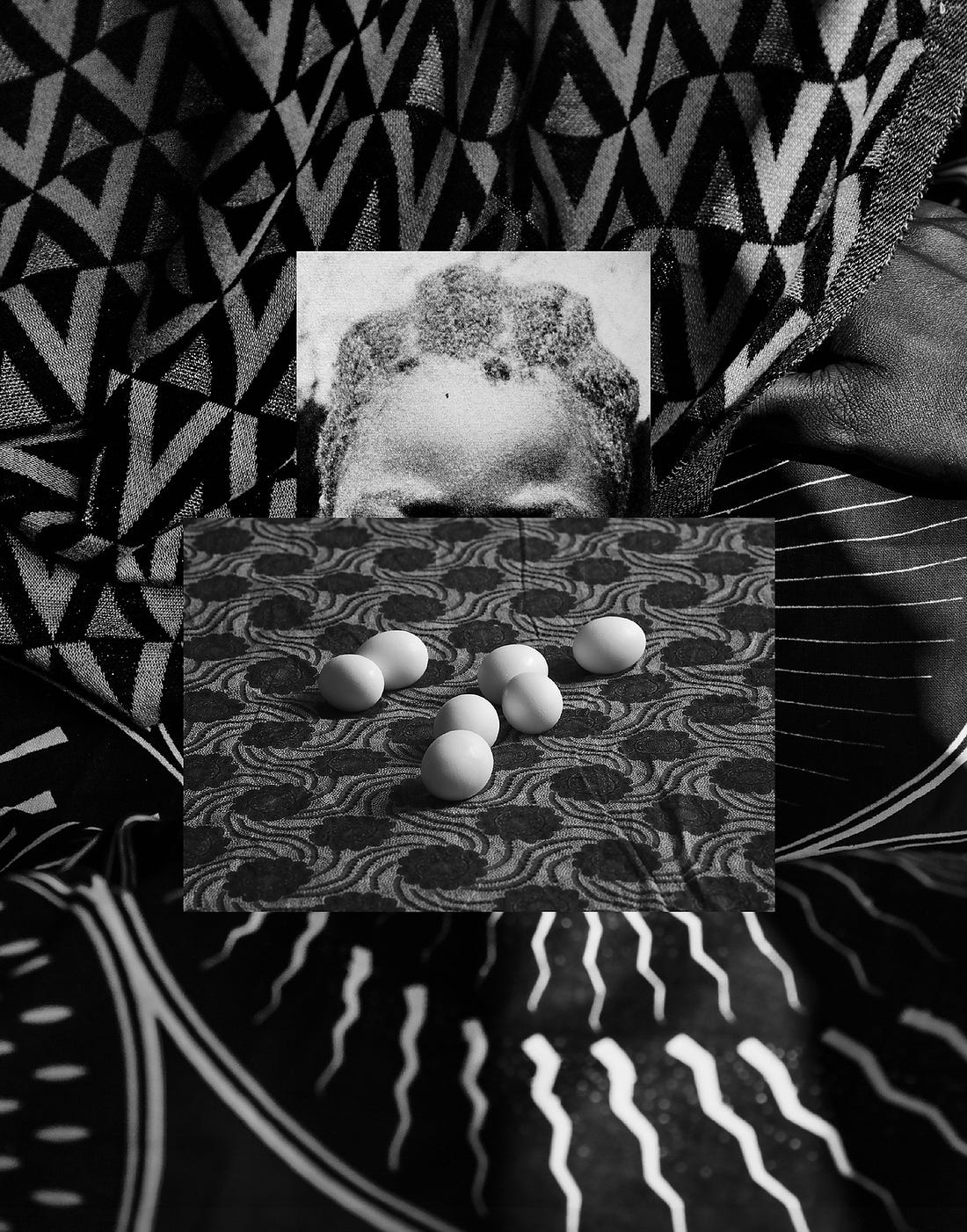

Alice Zoo: I’d like to start with the form of your book, which gathers many kinds of images and arranges them alongside one another in a dense collage. Could you tell me about the process of bringing the images together like this, and how you landed on this form in the process of making the book, how it evolved? And why are you drawn to collage as a tool, more generally? I’m thinking, too, of your work Passports. Keisha Scarville: When given the opportunity to make a book, I knew that I didn't want a book that was a catalog of my own images. I have nothing against catalogs or monographs that are highly specific and focused on the artist/photographer’s work, but that wasn’t what I was envisioning for my first book. I wanted to create a book where my work was presented alongside all the images that have inspired me or have informed the way I think about photography. There are themes that I am often working with in my own images, specifically around the body and place (or ways in which bodies are placed). Every time I approach the act of making an image, there is this abundant ecosystem of work at play. I truly wanted the book to be a piece unto itself where I could engage the poetics of a book format. There are temporal possibilities that I find to be unique to a book versus a wall, gallery space or screen. I started to learn that creating a book is like designing a map. The pages are navigational. Each turn moves us through a visual experience. Michael Mack gave me the freedom and time to work on it. My first step was spending time gathering everything that I wanted to include — a netting of memory and existence. There are images that I grew up with, images from my own family archive, screenshots from some of my favorite films, my own words and doodles from moments when I am contemplating time. The book opens and closes with detailed images of the seawall in Guyana, South America, where my family is from. I am incredibly captivated by this structure, which is meant to protect the coast from rising waters. I thought it would be fitting to start and end with this. The book then moves into the singular presentation of my images. Then, I wanted the flow to break as we got closer to the center, where I embrace density with brief pauses of words. I found myself thinking more like a filmmaker than a photographer. I enjoy the ways in which collage lends itself to temporal stitching. I think I am drawn to how collage inherently reorders and creates its own visual language. In the book, every moment is now, regardless of when the image was taken. There are a few images of deceased family members and other individuals. I was thinking about collage as an act of embracing the aliveness of the image. I think collage operates slightly differently in the Passports series. There, collage — and processes like painting and other media — become a way to uncover or activate what is latent within the image, which is otherwise deceptively neutral.

AZ: I appreciate the idea of the ecosystem of a work or a mode of thinking. It feels like the frameworks you’re thinking with — maps, nets — point to a notion of the artist not as solitary but as interdependent, connected (to other artists, to family, to broader social context) and reliant on mutuality, as indeed we all are, artists or otherwise. It seems like the idea of collectivity within the context of the sole practitioner is ever more rare in today’s creative landscape. And, like an ecosystem, the book feels like something very shifting and alive. I wonder if you still work with the images in the book, whether you continue to use and rearrange them within your wider practice, or whether publishing the book felt like it ‘set’ them in some way — like they found their place, and you could then move on from those particular images to make and draw from new ones. KS: I have continued working with some of the images in different capacities. Other images feel very connected to their presentation in the book. The book opened up a new way of thinking about photography for me. I recently did an exhibition at Webber Gallery in LA based on the book. It was a challenge to take the book and make it into physical, navigational space. Some images were shown very differently from how they are presented in the book. I think as we evolve as people, our perception also shifts, and the way I see my images is always changing. I think I tend to resist thinking of images of being fixed in any particular time or place. Before the book, I had been questioning photography’s capacities. I was very invested in documentary photography and finding the poetic in the everyday. I think I still have those beliefs, but after my mother passed away in 2015 I became more interested in photography’s relationship to absence, and its capability to capture what may not be readily apparent. How does the camera engage latency, and what are the relational conversations between the archive and the present. I released myself from thinking about my work as consisting of defined, separate projects. Working on the book definitely solidified this new thinking for myself.

AZ: I can see how, retroactively, it’s possible to work with images in such a way that old definitions and/or hierarchies collapse; but as you go on to make new works, now, I’m curious how that porousness functions in practice. Do you still find yourself moving through particular cycles or surges of interest at certain moments, currents that previously might have coalesced into separate projects? Or is everything now part of the same, undifferentiated flow? I’m also wondering how that mode actually feels to implement — is it always fruitful, or does the undefined-ness ever feel hard to manage? KS: This is a difficult question to answer. I do love that I have released myself from concentrating on a particular body of work. I find myself operating more intuitively. I make images based on what is percolating for me at the time. This is also coupled with my constant return to the archive and interest in visual culture. All the images are orbiting around me at any given time. I will admit that since making the book, I vacillate between feeling liberated and being overwhelmed. This way of being is often tested, particularly in spaces where labels, containers, and clear legibility are required for work to be understood. AZ: Why did it feel important to decentre your work, placing your own photographs amongst the archive, alongside others? And can you tell me some more about the process of enacting that decision? KS: Honestly, it came about from exhaustion. I have been making images for quite some time and I started to realize that every project, every image, held elements of previous gestures/interests/explorations. The attempts to try to place them in distinct categories of investigation was tiresome. I longed for a language that was more porous, less definitive, and that made space for other visual encounters aside from the images I am making. I was inspired by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa and Deana Lawson. Their work was the first time I saw references highlighted in the presentation of the work. There was something incredibly energizing about this. Though photographs are inherently still, they are not static. The book was the first place where I started to lay out all the images together and create a sort of tapestry.

AZ: I’d like to know more about the fragments of text that run throughout the book, which feel like another connective thread: where they came from, how they found their way into the book, at what stage, and so on. KS: They were things that I was doodling. This was something I’d been doing for a really long time, thinking about home, but also thinking about time. I had all these things written down, and I wanted them to be Haiku-like, for them to feel like fragments. During one of my meetings with Michael, at MACK, I had shared it with him, and he said we should use this for the title of the book. And he told me to just keep writing. So I just kept writing, and thinking about my ideas of home, like: what are these gestures that bring me back to home? What are the gestures that conjure another person in my life? What are the ways in which I’m thinking about how time is mapped? At a certain point I wanted to add dates. Each of the dates represents the year that someone in my family was born, or the year someone in my family passed away. That was the thinking behind the text. And I think part of it, also, was that as I was laying everything out, I felt like the work was so dense; I wanted to create a space to pause, and to linger in the space that’s created by the words. AZ: You’ve said that the work is an exploration of the forces and currents that have shaped you. I was wondering about whether you felt that the process of making the work, and turning it into a book, had shaped you in turn, in some way? KS: The book has had so many reverberations. There are so many things that I hadn’t expected. The book was kind of the first place where I really allowed myself to be free. And, in a lot of ways, it was taking the ways in which I’m thinking, and working, and understanding photography, and understanding all the things that build my relationship to photography, and putting them into this book in a way that was free of any preconceived ideas about what it needed to be, or how it needed to look like something else. So yes, obviously it’s affected the way I’ve thought about photography, and thought about how things are categorised. I think in my teaching, I’ve always encouraged students to be in the process. Because I work with students who are graduating, I often see the way that they have many ideas, but they’re also responding to market, and responding to how they need to present themselves. There is a validity to that, on some level, but I also think that there’s something about the beauty of being in process. How do you create space for dreaming, and spaces for making mistakes? It doesn’t necessarily have to be packaged neatly. I’m interested in that, and I encourage my students to think about that as well. Recently I had a conversation a professor who was teaching a course in China, and she assigned my book. She said that on the first day they sat down to talk about it, a lot of people in the class didn’t know what to make of it. I thought that was interesting, actually. I liked that. I thought, well — they don’t have to make anything of it. It doesn’t have to be something that’s easily understood, or digestible, or that makes sense, or that speaks to them. Having those conversations does make me think about legibility in photography, especially in the space that we’re in now, where the photograph has to translate, it has to speak to something. And then in those moments when maybe it’s not all given — what do you do?

AZ: This comes back to what you were saying about freedom — that it’s difficult to maintain. KS: Yes. I’ve come to this place where I’m responding to stagnancy, and how to move through it. I’m thinking about the ways in which photography, and how it’s presented, becomes a bit stagnant. I see it happening within certain spaces, where a photographer, or a way of presenting work, gets pushed forward. There’s a kind of stylising, and a way in which certain photographers get presented and presented and presented, over and over again, and so everyone starts to try to mimic that style. There should be such a vast multiplicity of ways that photography can be presented and discussed, and so sometimes I feel that talking about a handful of the same photographers, over and over again, creates a stagnancy in terms of what new languages can come out of the medium. I’m not really interested in talking about Henri Cartier-Bresson again. There’s a validity to it, but there are certain things I want to move past, or maybe just broaden. I want to know: what are the things that trouble a photographer? What are the things that they’re wrestling with, and how does that show up?

Every month I ask each artist to recommend a favourite book or two: fiction, non-fiction, plays, poems. My hope is that, if you enjoyed the above conversation, this might be a way for it to continue. Keisha Scarville’s recommended reading: Palace of the Peacock — Wilson Harris Dub — Alexis Pauline Gumbs Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic As Power — Audre Lorde A Mercy — Toni Morrison Black Quantum Futurism: Theory and Practice by Rasheedah Phillips A huge thanks to Keisha Scarville, and to you for reading. You can reply to this email if you have any thoughts you’d like to share directly, or you can write a comment below: You’re currently a free subscriber to INTERLOPER. This is a reader-supported publication, and I’m so grateful for all paid subscriptions; they help me continue to work on this project. If you enjoy the newsletter, consider upgrading. If you’d like a paid subscription but can’t afford it, reply to this email and I’ll comp you one, no questions asked. |

A Conversation with Keisha Scarville

06:02 |

Assinar:

Postar comentários (Atom)

0 comentários:

Postar um comentário