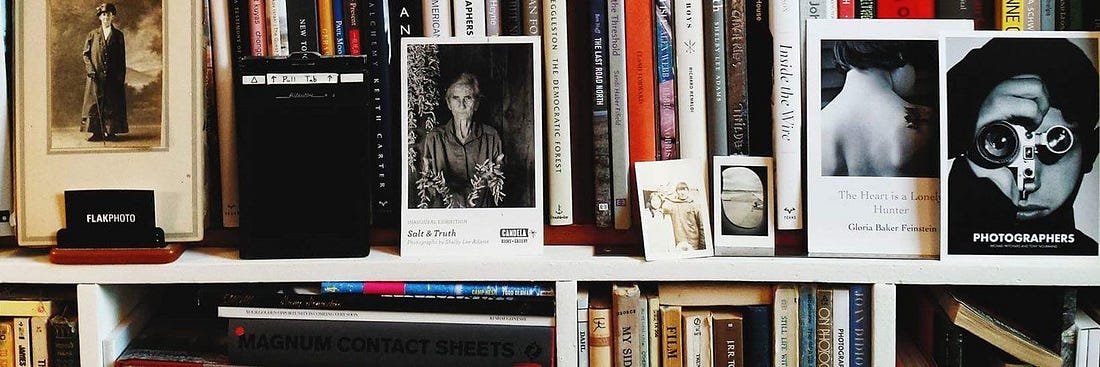

I launched a new feature this week — a Monday muse, if you will. Just a picture and some links to see more of that photographer’s work. Drop me a line if you’d like to contribute! I've been experimenting with Claude again recently and occasionally find myself asking it open questions to see what it thinks. I’ve been surprised by how engaged I am in the process; these tools are definitely improving. Today, I asked: Does the camera lie? (I suppose a more important question is: Does Claude lie?) I found Claude's response enlightening, and I thought you might, too, so I’m sharing it with some minor edits. I know, this is Photography 101; consider it a mindwalk for your photo self. Please let me know your thoughts. Cheers! — AA

The following text was generated by Claude AI and lightly edited for length and clarity. I added links for context, but have not fact-checked every claim for accuracy. I appreciate the ideas explored here. I hope you do, too!Does the Camera Lie?The question sounds simple. It isn’t. It cuts to the heart of epistemology—the study of what knowledge is, how we acquire it, and whether we can trust it. Photography occupies a uniquely uncomfortable intersection: it appears to show us the world directly, yet we know it doesn’t. Let’s work through the layers. The Naive Realist Position: The Camera Doesn’t LieThe folk theory of photography is roughly this: a camera is a machine. It has no agenda, no emotions, no memory. It records photons that bounced off real surfaces at a real moment in time. In that sense, it seems to have a stronger claim to truth than any human witness, who is fallible, biased, and motivated. This view has serious philosophical backing. The philosopher Kendall Walton argued that photographs are transparent — that when you look at a photograph of the Eiffel Tower, you are, in a meaningful sense, actually seeing the Eiffel Tower, mediated by a causal chain rather than by someone’s imagination. On this view, the photograph is more akin to a window or a mirror than to a painting. Its connection to reality is mechanical and indexical — the image is causally produced by the thing it depicts. This distinguishes it from, say, a drawing, which is entirely mediated by the artist’s choices. The philosopher C.S. Peirce’s semiotics is also useful here. He distinguished between symbols (arbitrary signs, like words), icons (signs that resemble what they represent, like diagrams), and indexes (signs caused by what they represent, like smoke caused by fire). A photograph is all three at once, but especially an index — it is physically caused by light reflecting off its subject. That causal link appears to confer a special epistemic status on it. The Constructivist Challenge: The Camera Always LiesBut the realist position quickly starts to crack when you examine it. Consider everything a photographer chooses before the shutter clicks: Framing. Every photograph excludes more than it includes. The frame is a decision — what’s in, what’s out. A photograph of a smiling crowd at a rally is a true image, but if you pull back, there might be protestors fifty feet away. The truth it captures is real but radically incomplete. The decisive moment. Henri Cartier-Bresson famously described photography as capturing “the decisive moment,” implying that, among the thousands of moments available, one is chosen. A subject captured mid-blink looks foolish; the same person a second later looks thoughtful. Both images are “true.” Neither is the whole truth. Lighting, angle, lens. A wide-angle lens distorts perspective. A telephoto lens compresses distance, making a crowd look denser than it is. Shooting from below makes a person look powerful; from above, diminished. These are not manipulations in the post-production sense — they are built into the act of taking the photograph. Context. The philosopher Roland Barthes, in his landmark work Camera Lucida, drew attention to how meaning in a photograph is always partly constructed by its context — the caption, the publication, the viewer’s knowledge. The same image of a man running can mean “fleeing danger” or “winning a race,” depending entirely on the framing outside the image itself. Barthes also introduced the concept of the punctum — the personal, subjective detail in a photograph that wounds or moves an individual viewer — which emphasizes the deeply subjective nature of photographic meaning, even when the image is ostensibly “objective.” Susan Sontag, in On Photography, pushed this further, arguing that photographs don’t so much capture reality as create it. The photograph of a famine doesn’t merely document suffering; it constructs a particular narrative of victimhood, passivity, and Western spectatorship. It aestheticizes suffering in ways that can actually distance the viewer from the reality it purports to show — the image substitutes for engagement. The Indexicality Problem Gets Worse: Digital PhotographyThe analog photograph had one advantage: the physical process. Silver halide crystals darkened because photons struck them. The connection to reality was literally chemical. Digital photography severs even that. A digital image is a numerical array — a matrix of values assigned by a sensor and processed by algorithms. Every smartphone photograph you’ve ever taken has been processed, sharpened, noise-reduced, color-corrected, and HDR-blended before you even see it on your screen. Apple and Google’s computational photography engines routinely composite multiple exposures into a single image. The “photograph” is already, in a technical sense, a construction. This is where deepfakes and generative AI become philosophically significant — not because they introduce lying into a previously honest medium, but because they expose the lie that was always there. If a manipulated image is indistinguishable from an unmanipulated one, it reveals that our trust in photographs was never really based on their intrinsic properties. It was based on social convention and the practical difficulty of manipulation. What Would It Even Mean to “Tell the Truth”?Here’s where it gets really interesting. Even if we stipulate a perfectly mechanical, unmanipulated image — no cropping, no filtering, no context — does it tell the truth? The problem of perspective. Every photograph is taken from somewhere, at some time, through some medium. There is no view from nowhere — what the philosopher Thomas Nagel called “the view from nowhere” — no impossible, neutral, God’s-eye perspective. Any image necessarily encodes a particular vantage point. This isn’t a flaw; it’s a logical necessity. But it means the photograph cannot claim to be “reality.” The problem of abstraction. Reality is four-dimensional — it unfolds in time, it has depth, it has smell, sound, and texture. A photograph is a two-dimensional static slice. It isn’t that photographs misrepresent time; it’s that they cannot represent time at all. They freeze a moment that, in reality, never existed. The philosopher Henri Bergson argued that our tendency to spatialize time — to treat it as a series of frozen frames — was a fundamental distortion of lived experience. Photography institutionalizes that distortion. The problem of interpretation. Even if we somehow solved all the above—neutral framing, unmanipulated image, no ambiguous context—the photograph must still be perceived and interpreted by a human mind. And human perception is not passive reception; it is active construction. We bring expectations, schemas, cultural knowledge, and emotional states to every image we see. Two people looking at the same photograph see, in a philosophically meaningful sense, different things. A Synthesis: The Camera Is an Honest LiarSo where does this leave us? I’d suggest the most defensible position is something like this: The camera is neither simply honest nor simply deceptive. It is a specific kind of truth-telling instrument that operates under constraints so profound that they amount to a form of structural deception—but a deception we can reason about and partially correct for. The photograph has a genuine indexical relationship to what was in front of the lens at that moment. That is real and meaningful. But it is a relationship between the sensor and a slice of reality — a slice defined by framing, timing, lens, light, processing, and context. The photograph tells the truth about what it captured, not about the world. The philosopher W.J.T. Mitchell put it well: images are not simply pictures of the world — they are arguments about the world. They don’t describe; they persuade. And persuasion is neither pure truth nor pure lie — it is a selective, interested, partial presentation of evidence. The most dangerous thing about photographs is not that they lie outright, but that they carry the authority of mechanical objectivity while functioning with the selectivity of rhetoric. We know that words are chosen. We are only beginning to culturally understand that images are, too. The Bottom LineDoes the camera lie? It depends on what we mean by “lie.” If lying requires intent, the camera cannot lie — it has none. If lying means “not telling the whole truth,” then the camera always lies, structurally, inevitably, as a matter of its very nature as a medium. And if truth means something like “adequate representation of reality,” then the camera tells a particular, partial, perspectival truth — which is, when you think about it, the only kind of truth any of us ever tell. The question “Does the camera lie?” might ultimately be less interesting than the question it opens up: What do we want from truth, and why did we ever think a machine could give it to us? Fascinating, no? I love this kind of intellectual wankery, but I know it’s not for everyone. After thanking Claude for its reply, I asked a final question: Can you show me a photograph that best illustrates a lying camera? Claude replied: Great challenge — one image above all others tends to come up in this philosophical conversation: Eddie Adams, “Saigon Execution,” 1968. It won the Pulitzer Prize and helped turn American public opinion against the Vietnam War. What it shows: South Vietnamese General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner in the street. The image is viscerally damning — an act of cold, summary murder, the general’s face utterly composed. What it doesn’t show — and this is where the camera “lies” — is almost everything that gives the moment meaning. The prisoner, Nguyễn Văn Lém, had allegedly just executed a South Vietnamese officer and his entire family, including children, that same morning. General Loan was operating in the chaos of the Tet Offensive, in a city under sudden attack, with no functioning judicial system available to him. Adams himself spent the rest of his life tormented by the image. He later wrote that the general “shot the enemy; I shot the general with my camera. Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world. People believe them, but photographs do lie, even without manipulation.” He personally apologized to Loan’s family after the general died. The photograph is not falsified. Nothing was staged, deceptively cropped, or manipulated. Every pixel is “true.” And yet it produced, in most viewers, a conclusion — this man is a monster — that Adams himself believed was profoundly unjust. It is perhaps the single most powerful real-world demonstration of every point made in the philosophical discussion: the frozen moment, the missing context, and the indexical authority that masks rhetorical force. The camera told the truth about one-thirtieth of a second, and lied about a man’s entire character. I found all of this fascinating, and it was good to spend time considering these ideas, especially given the Post-Truth America we are living in today. Of course, there isn’t an easy answer to this question, but I would value your thoughts. Feel free to leave me a comment or drop a note in our subscriber chat. I look forward to hearing from you.

One more thing… If you liked this post, you will enjoy Errol Morris’ 2011 book, Believing Is Seeing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography, which includes an excellent essay about Roger Fenton’s Crimean War photographs. I read it years ago and loved it. I’ll leave you with this: Lawrence Weschler interviewed Morris about Fenton’s Crimean War photographs for Public Books. I hope this philosophical talk hasn’t been too annoying. Have a great weekend, folks. Take care! Do you want to contribute photography or writing to FlakPhoto? Please feel free to email anytime. I’m always looking and love seeing new work. Cheers! |

Does the camera lie?

12:06 |

Assinar:

Postar comentários (Atom)

0 comentários:

Postar um comentário